Irish Traveller

- For other uses of the term see Travelers.

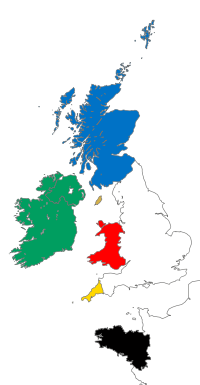

Irish Travellers (Irish: Lucht siúil) are a traditionally nomadic people of Irish origin with their own language and traditions, living predominantly in Ireland and Great Britain but also in the United States of America [1][2].

Traditionally called "Tinkers" [3], they refer to themselves as Minceir or Pavees in their own language or in Irish an Lucht Siúil, meaning literally "the walking people". The European Parliament Committee of Enquiry on Racism and Xenophobia found them to be amongst the most discriminated against ethnic groups [4] and yet their status remains insecure in the absence of widespread legal endorsement. [3]

Contents |

Origins

The historical origins of Travellers as a group has been a subject of academic and popular debate.[5] It was once widely believed that Travellers were descended from landowners or labourers who were made homeless by Oliver Cromwell's military campaign in Ireland and in the 1840s famine. However, their origins may be more complex and difficult to ascertain because through their history the Travellers have left no written records of their own. Others claim there is evidence of nomadic groups in Ireland in the 5th century, and by the 12th century the name Tynkler and Tynker emerged in reference to a group of nomads who maintained a separate identity, social organization, and dialect.[6]

Furthermore, even though all families claim ancient origins, not all families of the Travellers date back to the same point in time; some familes adopted Traveller customs centuries ago, while others did so in more modern times.[7]

Population

The 2006 census in Ireland reported the number of Irish Travellers as 22,369[8] Statistics for Irish Travellers in the UK do not exist although for the first time in 2011, the census will recognise Gypsies and Irish Travellers as distinct ethnic groups with specific needs. Recent estimates number both Roma Gypsies and Irish Travellers together at 300,000, and are based on local government caravan counts[9]

Language

Irish Travellers distinguish themselves from the settled communities of the countries in which they live by their own language and customs. The language is known as Shelta, and there are two dialects of this language, Gammon (or Gamin) and Cant. It has been dated back to the eighteenth century, but may be older than that.[10]

Customs and employment

Travellers are keen breeders of dogs such as greyhounds or lurchers and have a long-standing interest in horse trading. The main fairs associated with them are held annually at Ballinasloe in Ireland and Appleby in the U.K. They are often involved on the recycling of scrap metals, e.g. 60% of the raw material for Irish Steel is sourced from scrap metal, approximately 50% (75,000 metric tonnes) collected and segregated by the community at a value of over £1.5 million (Pavee Point 1993: 16). Such percentages for more valuable non-ferrous metals may be significantly greater. [11]

Cultural suspicion and conflict

Irish Travellers are recognised in British law as an ethnic group.[12] Ireland, however, does not recognise them as an ethnic group; rather, their legal status is that of a "social group".[13] An ethnic group is defined as one whose members identify with each other, usually on the basis of a presumed common genealogy or ancestry. Ethnic identity is also marked by the recognition from others of a group's distinctiveness and by common cultural, linguistic, religious, behavioural or biological traits.

Although now considered offensive by many, Travellers are often referred to by the terms "gypsies",[14] "diddycoy", "tinkers" or "knackers"[15]. These terms refer to services that were traditionally provided by them, tinkering (or tinsmithing), for example, being the mending of tin ware such as pots and pans and knackering being the acquisition of dead or old horses for slaughter. Other derogatory terms such as pikey[16] and gypo [17] or "gippo" [18] (derived from Gypsy) are also heard. "Diddycoy" is a Roma term for a child of mixed Roma and non-Roma parentage; as applied to the Travellers, it refers to the fact that they are not "Gypsy" by blood but have adopted a similar lifestyle.

Travellers are stereotyped as anti-social, drop-outs and misfits [19], notorious for their illegal settling on land not owned by them. [20] The Commission on Itinerancy, appointed in Ireland in 1960 under Charles Haughey, found that 'public brawling fuelled by excessive drinking further added to settled people's fear of Travellers ... feuding was felt to be the result of a dearth of pastimes and illiteracy, historically comparable to features of rural Irish life before the Famine'.[21] Their women, being just as likely to take part in brawling, along with other anti-social activities such as begging and intimidation, often find themselves victims within their own communities as well as in society at large. [22][23] Children are often grown up outside of normal educational systems. [20]

In Northern Ireland, such prejudices become sectarian, Travellers being seen as an "invasion from the south of Ireland" and politicised by Unionist politicians accusing them of "milking the Northern Irish economy" and threatened by the UDP. In Ireland, they have been subjected to killings, allegedly by IRA groups.[19] In many place they are denied access to public houses and business where "No Travellers" signs can be still seen. As recently as 1999, one Tory politician was reported as suggesting they should be "starved out of town". Families often have difficulties getting access to health, education and social services. [20]

Racial equality and discrimination

A complaint against Travellers in the United Kingdom is that of unauthorised Traveller sites being established on privately owned land or on council-owned land not designated for that purpose. Under the government's "Gypsy and Traveller Sites Grant", designated sites for Travellers' use are provided by the council, and funds are made available to local authorities for the construction of new sites and maintenance and extension of existing sites. However, Travellers also frequently make use of other, non-authorised sites, including public "common land" and private plots, including large fields. Travellers claim that there is an under-provision of authorised sites—the Gypsy Council estimates an under-provision amounts to insufficient sites for 3,500 people[24]—and that their use of non-authorised sites as an alternative is unavoidable.

Traveller advocates, along with the Commission for Racial Equality in the UK, counter that Travellers are a distinct ethnic group with an ancient history and claim that there is no statistical evidence that Traveller presence raises or lowers the local crime rate.

The struggle for equal rights for these transient people led to the passing of the Caravan Sites Act 1968 that for some time safeguarded their rights, lifestyle and culture in the UK. The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, however, repealed part II of the 1968 act, removing the duty on local authorities in the UK to provide sites for Travellers and giving them the power to close down existing sites.

The Georgia Governor's Office of Consumer Affairs issued a press release on March 14, 2007 titled "Irish Travelers Perpetuate a Tradition of Fraud".[25]

In Northern Ireland, opposition to Travellers' sites has been led by the Democratic Unionist Party. [19]

Health

It has long been recognised that the health of Irish Travellers is significantly poorer than that of the general population in Ireland. This is evidenced a 2007 report published in Ireland states that over half of Travellers do not live past the age of 39 years.[26]. Another government report of 1987 found:

From birth to old age, they have high mortality rates, particularly from accidents, metabolic and congenital problems, but also from other major causes of death. Female Travellers have especially high mortality compared to settled women.[27]

In 2007, the Department of Health and Children in the Republic of Ireland, in conjunction with the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety in Northern Ireland, commissioned the University College Dublin School of Public Health and Population Science to conduct a major cross-border study of Travellers' welfare. The Study, including a detailed census of Traveller population and an examination of their health status, is expected to take up to three years to complete.[28] Traveller women were “shocked” to discover rape could occur within marriage, and believed only physical violence constituted domestic violence, 2007 research revealed[29]

Genetic studies by Miriam Murphy, David Croke, and other researchers identified certain genetic diseases such as Galactosemia that are more common in the Irish Traveller population, involving identifiable allelic mutations that are rarer among the rest of the community. Two main hypotheses have arisen, speculating whether:

- this resulted from marriages made largely within and among the Traveller community, or

- suggesting descent from either an original Irish carrier long ago with ancestors unrelated to the rest of the Irish population.[30]

They concluded that: The fact that Q188R is the sole mutant allele among the Travellers as compared to the non-Traveller group may be the result of a founder effect in the isolation of a small group of the Irish population from their peers as founders of the Traveller sub-population. This would favour the second, endogenous, hypothesis of Traveller origins. No estimate was given for the date of the original mutation, but it is now clear that it mutated from other galactosemia-causing mutations that are found within the larger Irish population.

Demographics

An exact figure for the Traveller population in Ireland is unknown. A national census in 2006 put the figure in the Republic of Ireland at 22,400 constituting just over 0.5 percent of the population.[31] A further 1,700 to 2,000 are estimated to live in Northern Ireland.[32] However much concern has been expressed that this figure does not represent the true size of the Traveller population. In addition to Ireland, Travellers live in other parts of the world. The number of Travellers living in Great Britain is uncertain, with estimations ranging between 15,000 and 30,000.[33]

From the 2006 Irish census it was determined that 20,975 dwell in urban areas and 1,460 were living in rural areas. With an overall population of just 0.5% some areas were found to have a higher proportion, with Tuam, Galway Travellers constituting 7.71% of the population. There were found to be 9,301 Travellers in the 0-14 age range, comprising 41.5% and a further 3,406 of them were in the 15-24 age range, comprising 15.2%. Children of age range 0-17 comprised 48.7% of the Traveller population.

The birth rate of Irish Travellers has decreased since the 1990s, but they still have one of the highest birth rates in Europe. The birth rate for the Traveller community for the year 2005 was 33.32 per 1000, possibly the highest birth rate recorded for any community in Europe. By comparison, the Irish National Average was 15.0 in 2007.[34]

On average there are 10 times more driving fatalities within the Traveller community. At 22%, this represents the most common cause of death among Traveller males. Roughly 10 times more infants die under the age of two, while a third of Travellers die before the age of 25. In addition, 80% of Travellers die before the age of 65. Some 10% of Traveller children die before their second birthday, compared to just 1% of the general population. In Ireland, 2.6% of all deaths in the total population were for people aged under 25, versus 32% for the Travellers.[35][36]

In the USA, communities tend to be found in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi. [37]

Famous Irish Travellers

- Johnny Doran, one of the most influential uilleann pipers in the history of Irish music, active during the first half of the 20th century.

- John O'Donnell, a boxer.

- Tyson Fury, a boxer.

- Bartley Gorman was the "king" of the Gypsies and undefeated bareknuckle boxing champion until his death in 2002.

- Francie Barrett has been a professional boxer since August 2000, and now fights at light welterweight, out of Wembley, London.

- Paddy Keenan, piper, is a foundational member of the Bothy Band in the 1970s and a key figure in the transition of Irish traditional music into the world of Celtic-denominated music. He comes from a family of Traveller musicians and is perpetually on tour across much of the United States and Europe.[38]

- John Reilly was a traditional Irish singer and source of songs. During 2004's "Live at Vicar Street", recorded by newly-reformed Irish folk act Planxty, Christy Moore mentions hearing Reilly sing for the first time and calls it a "life changing" experience, going on to dedicate the song "As I Roved Out" to his memory.

- Margaret Barry was a Traveller from Cork who became a well known name on the London folk scene in the 1950s, with her distinctive singing style and idiosyncratic banjo accompaniment.

- Pecker Dunne is a well known Traveller and singer from Wexford, Ireland.[39]

- Michael Gomez, a professional boxer based in Manchester England, was born in an Irish Traveller family in Longford, Ireland.

In popular culture

Irish Travellers have been portrayed on numerous occasions in popular culture.

Documentaries

- My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding - A Channel 4 Documentary about Traveller weddings.

- Southpaw: The Francis Barrett Story — a documentary following Galway boxer Francis (Francie) Barrett for three years and showing Francie overcoming discrimination as he progresses up the amateur boxing ranks to eventually carry the Irish flag and box for Ireland at the age of 19 during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta.[40] This film won the Audience Prize at the 1999 New York Irish Film Festival.

- King Of The Gypsies (1995) - a documentary film about Bartley Gorman, undefeated Bareknuckle Champion of Great Britain & Ireland.

- Traveller, a documentary by Alen MacWeeney [41]

Movies

- Snatch — A 2000 film featuring Brad Pitt as a comically stereotyped "Pikey" who is also a bareknuckle boxing champion. [42]

- Into the West — A film that tells the story of two Traveller boys running away from their drab home in Dublin.

- The Field - a 1990 film in which farmer Bull McCabe's only son runs away with a family of travellers

- Man About Dog — A 2004 film featuring a group of Irish Traveller characters.

- Traveller — A 1997 film, starring Bill Paxton, Mark Wahlberg, and Julianna Margulies, about a man joining a group of nomadic con artists in rural North Carolina.

- Strength and Honour — A 2007 film deals with a man joining a Traveller boxing tournament in order to win money for his son's operation.

- Trojan Eddie – 1996 crime drama film directed by Gillies MacKinnon starring Stephen Rea, Richard Harris, Stuart Townsend, Aislín McGuckin, Brendan Gleeson and Sean McGinley. Soundtrack features Tinker's Lullaby, written and performed by Pecker Dunne.

Novels

- See You Down the Road by Kim Ablon Whitney - A novel about Travelers in the United States. Intended readership - Grade 9 up.[43]

- Fork in the Road, a novel by Denis Hamill [44]

- The Killing of the Tinkers, a novel by Ken Bruen [44]

- Traveller Wedding — An eNovel from film director Graham Jones narrated by a fictitious nomadic Irishwoman called Christine who is furious about the release of a violent videogame about a traveller wedding and determined to tell the story of her people more authentically.

- The Wheel of Time — Robert Jordan's series of fantasy novels featuring a group of nomadic people based on the Irish Travellers, the Tuatha'an, who share the name "Tinkers" and a reputation (portrayed in the books as largely undeserved) for petty theft.

- FightGame and Firefight by Kate Wild — teenage/young adult novels with a charismatic gypsy boy hero called Freedom Smith. They are thriller/sci fi based but they also deal with the real problems Gypsies and Travellers face.

- The Tent and Other Stories by Liam O'Flaherty. J. Cape (London, England), 1926.

TV series

- The Riches — An FX television series starring Eddie Izzard and Minnie Driver as Wayne and Dahlia Malloy, the father and mother of an American family of Irish Traveller con artists and thieves. The series revolves around their decision to steal the identities of a dead "buffer" family and hide out in their lavish mansion in suburban Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Star Trek: The Next Generation, Season 2, Episode 18, "Up the Long Ladder" (May 22, 1989) — In this episode of the television show, the Enterprise encounters a society, the Bringloidis, (cf. brionglóid: meaning "dream" in the Irish language), that was founded by humans who left Earth centuries earlier to found a colony. They appear to be descended from Irish Travellers, possessing their accented form of the English language and a culture that appears very similar.[45]

- Law & Order: Criminal Intent, Season 2, Episode 21, "Graansha" — This episode of the NBC television show focuses on the murder of a probation officer who springs from a family of Irish Travellers.

- The Riordans (1964–1979) — In this Irish television soap opera, many issues affecting the Traveller community were portrayed through the challenges faced by the Maher family.

- Glenroe (1983–2001) — A spin-off of The Riordans featuring the Connors, a family of settled travellers.

- Killinaskully — This RTÉ Irish sitcom features a Traveller character named Pa Connors, played by Pat Shortt.

- Pavee Lackeen (Traveller Girl) — A 2005 documentary-style film depicting the life of a young Traveller girl that features non-actors in the lead roles. Its director and co-writer, Perry Ogden, won an IFTA Award in the category of Breakthrough Talent.[46]

- Midsomer Murders, Episode 4, Series Two, Blood Will Out (1999) — This episode of the British television drama features a local magistrate in an English village attempting to oust Travellers from his jurisdiction by means of a paramilitary vigilante attack.

- Without a Trace — One episode of this CBS television show features a woman of Irish Traveller descent who had left the community and gone missing. Interestingly enough, this episode is one of the few on the show where the person had not been the victim of foul play but had instead simply decided to return to her birth community without informing anyone.

- Dragonsdawn – By Anne McCaffrey includes as major characters the Connell family who are part of a group of Irish Traveling folk.

- "Singin' Bernie Walsh" – Character created and played by Irish comedienne Katherine Lynch. Known for her album Friends In Hi Aces, her singles "Dundalk, Dundalk", "Don't Knock Knock 'Til You've Tried It" and "Stand By Your Van", Singin' Bernie Walsh featured in both of Lynch's RTE comedy series Wonderwomen and Working Girls which show her attempts at topping the Irish charts and achieving "inter-county-nental" fame.

- Jim Henson's The Storyteller – The Episode "Fearnot" is a folk tale of a youth in search of fear. He befriends a "Tinker" on his journey.

Theatre

- Mobile the Play - written and performed by Michael Collins and directed by Mick Rafferty

- The Trailer of Bridget Dinnigan - written and directed by Dylan Tighe

- The Tinker's Curse by Michael Harding [47]

- The Tinker's Wedding by J. M. Synge

- By the Bog of Cats (1998) by Marina Carr.

See also

|

|

References

Bibliography

- Bhreatnach, Aoife (2007). Becoming Conspicuous: Irish Travellers, Society and the State 1922-70. Dublin: University College Dublin Press. ISBN 1-904558-62-3.

- Bhreatnach, Aoife; Breathnach, Ciara (2006). Portraying Irish Travellers: histories and representations. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press. ISBN 9781847180551.

- Burke, Mary (2009). 'Tinkers': Synge and the Cultural History of the Irish Traveller. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-956646-1.

- Dillon, Eamon (2006). The Outsiders. Merlin Publishing. ISBN 1-903582-67-9.

- Drummond, Anthony; Hayes, Micheál (ed.); Acton, Thomas (ed.) (2006). "Cultural Denigration: Media representation of Irish Travellers as Criminal". Counter-Hegemony and the Postcolonial "Other". Cambridge Scholars Press: Cambridge. pp. 75–85. ISBN 1847180477

- Drummond, Anthony; Ồ hAodha, Micheál (2007). "The Construction of Irish Travellers (and Gypsies) as a Problem". Migrants and Memory: The Forgotten "Postcolonials”. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press. pp. 2–42. ISBN 9781847183446

- Drummond, Anthony (2007). Irish Travellers and the Criminal Justice Systems Across the Island of Ireland. University of Ulster (PhD thesis)

- Gmelch, George (1985). The Irish Tinkers: the urbanization of an itinerant people. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press. ISBN 0-88133-158-9.

- Gmelch, Sharon (1991). Nan: The Life of an Irish Travelling Woman. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press. ISBN 0-88133-602-5.

- Joyce, Nan; Farmar, Anna (ed.) (1985). Traveller: an autobiography. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 9780717113880

- Maher, Sean (1998). The Road to God Knows Where: A Memoir of a Travelling Boyhood. Dublin: Veritas Publications. ISBN 1-85390-314-0.

- Ó hAodha, Micheál; Acton, Thomas (eds.) (2007). Travellers, Gypsies, Roma: The Demonisation of Difference. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press. ISBN 9781847180551.

Notes and references

- ↑ Ethnicity and the American cemetery by Richard E. Meyer. 1993. "... though many of them crossed the Atlantic in centuries past to play their trade".

- ↑ Questioning Gypsy identity: ethnic narratives in Britain and America by Brian Belton

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Traveller, Nomadic and Migrant Education by Patrick Alan Danaher, Máirín Kenny, Judith Remy Leder

- ↑ Traveller, Nomadic and Migrant Education by Patrick Alan Danaher, Máirín Kenny, Judith Remy Leder. 2009. Page 119.

- ↑ Helleiner, Jane (2003). Irish Travellers: Racism and the Politics of Culture. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802086280. http://books.google.com/?id=Zr6VRPmZjV8C&pg=PA29&dq=origins+of+Irish+Travellers.

- ↑ Solidarity with Travellers, 2008, Sean O'Riain

- ↑ Sharon Gmelch, Nan: The Life of an Irish Travelling Woman, page 14

- ↑ Irish Census 2006

- ↑ Commission for Raciel Equality report into Gypsies and Irish Travellersin 2006

- ↑ Sharon Gmlech, op. cit., page 234.

- ↑ Recycling and the Traveller Economy (Income, Jobs and Wealth Creation), Dublin: Pavee Point Publications. 1993

- ↑ Commission for Racial Equality: Gypsies and Irish Travellers: The facts

- ↑ Irish Travellers Movement: Traveller Legal Resource Pack 2 - Traveller Culture

- ↑ "The Roma Empire". newsquest (sunday herald). 2009. http://www.sundayherald.com/mostpopular.var.2499923.mostviewed.the_roma_empire.php. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/08/world/tullamore-journal-travelers-tale-irish-nomads-make-little-headway.html?pagewanted=2

- ↑ Geoghegan, Tom (11 June 2008). "How offensive is the word 'pikey'?". BBC News Magazine. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/7446274.stm. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ Understanding the stigmatization of Gypsies: power and the dialectics of (dis) identification by R Powell. Housing, Theory and Society, 2008

- ↑ How the White Working Class Became 'Chav' J Preston - Whiteness and Class in Education, 2007

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Divided society: ethnic minorities and racism in Northern Ireland (Contemporary Irish Studies) by Paul Hainsworth. 1999

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Social work and Irish people in Britain: historical and contemporary responses to Irish children and families by Paul Michael Garrett. 2004.

- ↑ Bhreatnach, Aoife (2006). Becoming conspicuous: Irish travellers, society and the state, 1922-70. University College Dublin Press. pp. 108. ISBN 9781904558613. http://books.google.com/?id=yQd1AAAAMAAJ&dq=irish+travellers+feuding&q=+feuding#search_anchor.

- ↑ Irish Travellers: Racism and the Politics of Culture by Jane Helleiner. 2003. Page 163

- ↑ Women within the communities Tinkers: Synge and the cultural history of the Irish Traveller By Mary M. Burke

- ↑ BBC News: Councils 'must find Gypsy sites'

- ↑ Georgia Governor's Office of Consumer Affairs: Irish Travelers Perpetuate a Tradition of Fraud

- ↑ ireland.com - Breaking News - 50% of Travellers die before 39 - study

- ↑ "The Travellers' Health Status Study". Irish Dept. of Health. 1987. http://www.dohc.ie/about_us/divisions/social_inclusion/travellers_health_status_study_1987.pdf?direct=1. Retrieved 2009-06-15. p24

- ↑ "Minister Harney Launches All-Ireland Traveller Health Study". UCD. 10 July 2007. http://www.ucd.ie/news/july07/100707_traveller.html. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2009/1128/1224259619132.html

- ↑ Miriam Murphy, Brian McHugh, Orna Tighe, Philip Mayne, Charles O'Neill, Eileen Naughten and David T Croke. Genetic basis of transferase-deficient galactosaemia in Ireland and the population history of the Irish Travellers. European journal of Human Genetics. July 1999, Volume 7, Number 5, Pages 549-554.

- ↑ "Press Release Equality in Ireland 2007". News and Events. Central Statistics Office Ireland. http://www.cso.ie/newsevents/pr_equalityinireland2007.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ↑ Redmond, Andrea (2008). "‘Out of Site, Out of Mind’: An Historical Overview of Accommodating Irish Travellers’ Nomadic Culture in Northern Ireland". Community Relations Council (CRC). pp. 1, 71. http://www.community-relations.org.uk/fs/doc/shared-space-issue-chapter5-59-73-web.pdf. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ↑ Irish Medical Journal "Traveller Health: A National Strategy 2002-2005". http://www.imj.ie/Issue_detail.aspx?pid=2395&type=Contents&searchString=travellers Irish Medical Journal.

- ↑ http://www.cso.ie/census/census2006results/volume_5/Tables_12_to_22.pdf

- ↑ Life expectancy of Irish travellers still at 1940s levels despite economic boom - Europe, World - The Independent

- ↑ The Irish Times - Mon, Jun 25, 2007 - 50% of Travellers die before 39 - study

- ↑ License To Steal, Traveling Con Artists, Their Games, Their Rules - Your Money by Dennis Marlock & John Dowling, Paladin Press, 1994, Boulder, CO.

- ↑ "About Paddy". http://www.paddykeenan.com/about.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ↑ Ballad Biographies of Irish Folk Singers

- ↑ Imdb: Southpaw: The Francis Barrett Story

- ↑ http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/indelible_macweeney.html

- ↑ Affecting Irishness: Negotiating Cultural Identity Within and Beyond the Nation by James P. Byrne, Padraig Kirwan, Michael O'Sullivan

- ↑ Whitney, Kim Ablon (2005). See You Down the Road (reprint ed.). Laurel-Leaf. ISBN 9780440238096. http://books.google.com/?id=Vtl3_gRyEb8C&q=See+You+Down+the+Road+by+Kim+Ablon+Whitney&dq=See+You+Down+the+Road+by+Kim+Ablon+Whitney. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Affecting Irishness: Negotiating Cultural Identity Within and Beyond the Nation By James P. Byrne, Padraig Kirwan, Michael O'Sullivan

- ↑ "Up The Long Ladder (episode) see comment attrib. to script-writer Melinda Snodgrass". WIKJA. http://memory-alpha.org/en/wiki/Up_The_Long_Ladder_(episode). Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Stardom for Irish Traveller girl [1]

- ↑ Playwright gives voice to Irish travellers by Barbara Lewis [2]

External links

- Irish Radio Documentary

- Traveller Heritage and Photo Site from Navan Travellers Workshops

- Irish Travellers' Movement

- Pavee Point Travellers Centre

- National Association of Travellers' Centres

- Voice of the Traveller

- Bibliography of Irish Travellers sources - University of Liverpool

- Historical Resources for Research into the Social, Economic and Cultural History of Irish Travellers

- Traveller and Roma Collection at the University of Limerick

- Irish Medical Journal article "Traveller Health: A National Strategy 2002-2005"

- Francie Barrett boxing profile

- Official site for movie - Pavee Lackeen: The Traveller Girl

- The Travellers: Ireland's Ethnic Minority

- The site of the French office of study NBNS, specialized in the reception of the Travellers in France, country where the reception of the Travellers people is centred by law.

- Interview with local expert on Dale Farm

- London Gypsy and Travellers Unit, Representing Traveller's issues in North and East London

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||